The now annual Christmas eve carol concert held in the church brought to an end a relatively quiet year for the village. Curiously the parish magazine made little if any mention of the clouds of war that were by then looming on the horizon, infact the hostilities that first announced it’s genesis seem to have surprised everyone. It didn’t of course and even HG Wells once said that “every intelligent man knew” but the more important things in life still carried on as usual, Salisbury cathedral improved it’s lighting system and parochially Baydon continued with their church organ fund and Aldbourne not only rehung the church bells but also re-gilded the clockface. The first few months of 1914 seem to have passed by at life’s normally blisteringly slow pace. English society had long been brought up to believe that they were secure in the hands of their armies and as our shores had not been threatened seriously for nearly one hundred years why should this time be any different? The M.T. did of course relate news of fighting but it was not until the July issues that any interest appeared to be taken in events that had started to occur though even then one article actually stated ‘……. the great war, the like the world has never seen’, In no way could that writer have ever realised just how prophetic his words were to become.

One of the earliest indications that affairs might be amiss could be seen in an advert announcing the cancellation of the Pewsey carnival. (matters must have been getting serious) and even Newbury cancelled its band contest but then nearly all the village reports began to tell of the ‘sons’ that had gone off to fight. Patriotic young men enlisted by the thousand, keen to be in on any action before the coming Christmas as it would ” all be over by then ‘. By the end of that November two of Aldbourne’s men already lay dead.

In essence Britain sent four very diverse types of army. The first consisted of our most battle hardened and experienced soldiers who formed the British Expeditionary Forces but incredulously by the end of the first few months of 1914 some 90% of them were either wounded, missing or dead. The next body of men to go in was of territorial form but by the end of 1915 they too were more or less all dead as well. The boys who had rushed to enlist for King and country in 1914 and who had spent some two years in training were the lambs who were the bulk of the third who then marched into the raging inferno that by then beckoned them. Conscription did not begin till 1916 and those that were then coerced made up the nature of forth.

Although intentions had been noble how different any realities were. Visions of a quick victory soon perished and the conditions enjoyed by those men can never be overstated and never must be, for trench warfare must surely be the most afflictive type of existence one could ever experience. Certainly the trenches that created the Western front were some 450 miles of indescribable hell, nay Hell would be far more preferable. Being cold, wet, hungry and totally exhausted would be the least of our lads torments. Try to conceive clothes so full of lice that they could and often did continue to move when you took them off or the pain of feet literally rotting away due to being immersed for days on end in mud, blood and water. Being deafened from near continuous shelling or the continuous threat of the “grim reaper” (machine guns) when you went yet again over the top or the fear of just being blown into three, four or even a thousand little pieces was nothing to what must of been the most hideous death of any, that of being gassed. The agonising pain of your lungs quite literally dissolving away and then finally drowning in a yellow blood stained froth is exactly what occurred. If you were lucky to survive to ‘tell the tale’ and finally return home your memories might haunt you forever. Perhaps the memory of the rats, fat with the abundance of ‘food’ that abounded by the million or else the putrefying stench of rotting flesh would and did haunt many for the rest of their lives. Even to this day when one walks out into those killing fields there is a sadness that prevails, an atmosphere that has to be experienced to be believed.

It has been said that the band dispersed during that time but this too is not quite as straight and clear cut as that might suggest. Although there are no mentions of any banding activities in any of our church magazines, there are several to be found mentioned in the local paper. A report in January 1915 stated “it is much regretted that the band is practically dissolved”, it also added “it is a pity to let them fall through, now they have reached their present eminence”. Albert Stacey did indeed have difficulty in raising a band as most of his players had enlisted. Many of our village men seem to having joined up with the 6th and 7th Wiltshire regiments, an article mentioned that the 7th Wilts regimental band played every Saturday in the “Salonika (Turkey) battlefields”.

The band still maintained its presence in the hospital parade and when two squads of the Derbyshire Yeomenary Regiments were stationed in the village, our band led a parade that included them in a church service where “very well they looked in their smart uniforms”. By 1915 they had to join forces with the Ramsbury PM band for the hospital parade as local bandsmen were “doing their bit”. Albert was able to put on a show for an Xmas concert the report stating that they deserved “great credit”. I think it probable that after their initial training period and before actually being sent abroad, some men came home on leave and it was then that this concert was held. The sum of £4-6s was raised and was shared between parents to pass on to their soldier sons. The report also tells us that “only” 43 lads had left our village at this time, by the end of 1917 some 190 men had “now gone”. Thomas Arthur Palmer remembered playing at a send off in 1915 for three reservists, he was then aged fourteen and these young boys along with just one or two men made up the remnants of a much decimated band that carried on for much of that war.

While many of our bandsmen did join up several didn’t due mainly to being in occupations considered too important to the war effort. We can only guess on the reasons why the men left here eventually stopped playing altogether, perhaps their time was taken up with more important tasks or it may be simply that they did not wish to be seen to be having an easy time or enjoying themselves too much and so jeopardise any appeals to the tribunals they might make or create any ill feelings within the village.

1916 also seems to be a fairly busy year for a band that didn’t exist for a whist drive was held on behalf of both the band and the nurses fund. A later event raised money for the church organ fund, the important things in life just didn’t go away did they? In the hospital Sunday report Albert is said to have “obtained the services of a few of the members (several having joined the army) and played excellent music”. HB Sheppard also organised a concert for the OAP tea party that included the band in the entertainment that followed.

The slaughter of the 43 men undoubtedly depredated not only the families but the whole of this small community. Though this was not the first (nor last) time Aldbourne’s men went off to fight in a war this was the first to interrupt Aldbourne’s peace and quiet since the two civil war skirmishes that occurred some two hundred and fifty years earlier.

The first death of one of Aldbourne’s “sons” occurred in 1914. Seaman Leslie Aldridge was serving onboard the SS Vedra when, laden with submarine fuel, she was blown up and sunk but it was in 1916 when news came of the first death of a bandsman. William Thomas Dew private 21234 6th Wilts battalion died of wounds received on Friday 3rd of November. Billy was only 23 years old and has no known grave, though he is commemorated on the Somme`s Theipval memorial. In 1917 John and Ann Dew, his parents, had this poem printed in his memory.

We prayed that God would not let him fall,

but fortune failed in the strife;

as he went forth with a heart so bold,

to answer his country’s call

A year has passed,

and still the wound is sore,

he did his duty to the last,

we miss him more and more.

During the late summer of 1916 news was received that baritone player John Orchard 3186, sergeant in the 8th battalion Kings Royal Rifles, had been awarded the D.C.M, in fact this was only one of several that were accorded to village men. A proud moment for his family, his father was John Orchard the chair factory proprietor. Young “Jack” had led the first wave of his company in an assault on enemy troops and although wounded he had held out for two hours before returning with two prisoners. Sadly his family’s rejoicing was short-lived as John was killed on Friday August 24th 1917 aged 23 . He is buried at the Hooge crater cemetery in Belgium though a military headstone can be seen in our own churchyard.

1917 seems to be the year that the band disbanded proper with no mentions being made again of them until 1919. The problems had by one bandsman might confirm that it was best to leave well alone and stop all banding till hostilities ceased. Thomas Dixon Barnes made claim that as he was the only village haulier to go to Hungerford he should be made exempt from military duties. An exceedingly irate letter appeared in 1918 written by a very upset wife indeed concerning a petition that had been put together by villagers in an attempt to stop Tommy’s call up. In it the lady fiercely criticised Tommy’s military absence and his reply was of course then printed. Tommy stated that his job consisted of more than just driving a horse for a few hours each day such as the lady had implied. He described his occupation in some detail telling that he had to “carter four horses daily” and “weigh up 7-8 tons of coal” and “deliver” and “sell it”. He intimated that this did not include his many other sundry duties.

However village events still had to continue so without their own men to call on the Swindon PM band was engaged to lead the hospital parade, it cost £2-2s for the brake hire to transport them here and back.

The following list is compiled from information taken from the Marlborough Times and our Aldbourne Parish Magazine.

Church Magazine.

1916 Military personnel from Chiseldon camp gave a concert in the church.

1917 Military personnel from Chiseldon camp gave a concert in the school room. “A concert was given in the church schools on Wednesday June 8th, by the soldiers from Chiseldon Camp. An excellent and varied program was gone through, and from start to finish the interest of the audience was maintained. Everyone was deservedly applauded and the writer can confidently say that it was by far the best concert he has attended in the county of Wilts”. It was apparently also a “real tonic” to those present. This report was written by the Reverend William Butler and praises this concert so highly that I would have thought that the band members left in the village would be quite put out by his comments, but perhaps they agreed with him.

Marlborough Times entries.

1915

A band concert in aid of village soldiers.

Aldbourne band in hospital Sunday parade.

Aldbourne band Xmas concert.

1916

Whist drive in aid of Aldbourne band and Nurse fund.

Band concert in aid of the church organ fund.

Aldbourne band play in the hospital parade.

Swindon Gorse Hill band play in village on hospital day.

In 1918, three young men, George Hull, Fred Sheppard and Jesse Emberlain, walked over the hill to Marlborough with intentions of signing up. Both George and Fred were accepted, though they did only light duty’s and returned safely, but Jesse was refused entry as he was deemed too young. He was refused again in 1939 because by then he was not only considered too old but he was also still in a protected occupation. Even in his last year of life at the age of 91 he still seemed to be angry about the way he had been excluded from duty. With guilty feelings still running around inside him, he told me that he felt he had failed not only his village but his family and friends. Men like Jesse Emberlain never failed anyone, for his work was just as important as any. Perhaps the land girls and men who stood watching when our village paraded in 1995 in celebration of the last armistice should have been included in that procession too?

Many events, including concerts, were held to raise money for the village wool club fund. They subsidised the knitting club that made items such as balaclavas, gloves and underwear that were sorely needed in the trenches. Finished garments were left at Ivy house, where any callers could select what they needed to send to their loved ones free of charge. 1d each a week was also donated by villagers to secure the wool supply.

Over 5,000 Wiltshiremen were slaughtered in that war. Aldbourne dispatched some 190 of its men and tragically 43 never returned, 5 of the dead were bandsmen. What little we know of Billy Dew and Jack Orchard has already been told but facts on the other three were nigh on impossible to ascertain as well.

Chummy Westal, the bands euphonium player, can be seen on photos dating 1909 to 1914. It was not possible to ascertain his christian name as he was always known by his nickname. No obituary was written in fact even his death went unannounced and I was unable to find anyone who could tell me which of the two Westals that were killed was Chummy, therefore I have to list them both. TC Westal 10313 gunner in the Royal Marine artillery died Saturday 10th august 1918 and is buried in the Port Charlotte United Freechurch on the Isle of Islay, Argyllshire and CE Westal gunner 198546 A batt 103 Royal Field artillery D 22nd of October 1917 and is buried at La Clyte military cemetery Heuvelland, Belgium.

Frank Henry Wakefield played with the band as a young lad and was included as a young soloist in a concert report in 1903. He had been encouraged by his father to become a full time soldier and had joined the 2nd Wilts regiment well before the onset of the war rising to the rank of corporal 26450. his father John had been a survivor of Robert’s famous march to Kandahar, and his sister Winnifred married Alfred Jerram in 1919. Frank was killed on Thursday, March 21st 1918 and is buried at Savy british cemetery Aisne, France.

Richard John Loveday had joined the 6th batt Wiltshire regiment and was killed on the 29th April 1918. He was the second son of William Loveday of the Lottage iron foundry works. His obituary told that although he had been wounded twice the “third bullet had proved fatal”. He is buried at the Arneke british cemetery, France.

Bandsmen who returned safely were Fred, Frank, Wilf and George Jerram, George Hull, Walter Barnes, Fred Barnes and Fred Sheppard. As some of the bandsmen remain anonymous to us they will have to remain forever unidentified, more may have been killed but if so we will never know. Over the breadth of the country numerous bandsmen sacrificed their lives and in 1926 J Henry Iles erected a plaque to the memory of our country’s bandsmen. It’s nice to know that even our village lads are included.

In later years another of our bandsmen was to suffer as much as any as a prisoner of war. Cyril John Palmer was captured in Italy and forced marched, via several Stalag POW camps to Poland to work as forced labour in coal mines. His was an horrific war, often witnessing obscenities no man should. Cyril lived to see another day though he could never again eat beetroot having once had to survive on little else. Always a gentleman and a most modest man he was never heard moaning of his lot, a lesson for us all perhaps.

Walter Young Barnes had been living in Toronto when the war started having gone there to find work just a couple of years earlier. On the outbreak of war “Pelly” immediately joined the 34th Canadian infantry brigade and of course their band. Shortly afterwards he returned to Britain where he transferred to the Royal Engineers. Pelly served on the Western front for three years eventually suffering a nervous breakdown after which he was discharged from his duties.

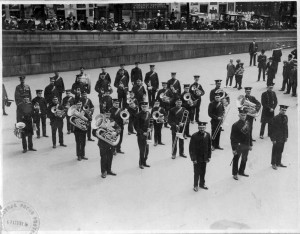

Its been said that our bandsmen were involved in the forming of the first Wiltshire Regimental Band. Certainly Frank and Fred Jerram and Fred Barnes took their beloved instruments with them and it is of course possible. On a picture taken in France c1915 the two Jerram brothers and Fred Barnes can be seen as members of a band formed from men of various regiments for a visit by Earl Haig.

Several of our bandsmen who were eligible for military duties made petition to the appeal committee for exemption. Albert Stacey was a village baker and told in one of his several appeals that he baked 6 bags of flour a week. We’ve already read about TDBarnes but Edward Sheppard and Albert Gregory were two others who were successful in their appeals as carter’s too. Fred Alder snr had a lucky escape, as he also claimed to be a carter and an agricultural labourer (for J Cook) but even though he was fifty years old his appeal in 1918 was adjourned till a later date. For him the war probably couldn’t finish soon enough and luckily for him it did.

Bonnie Barrett “an old soldier suffering from malaria”, was described as a water engineer and agricultural labourer for Sir James Currie of Upham house and so was also made exempt as he had already done his bit.

An interesting article in 1920 told us that during that war the band had loaned to another band several of their instruments but that on being returned they had been found to have been badly damaged. I presume these were the instruments taken to the battle fields. According to this article at the start of the war the band had an instrument fund debt of £35 but now they needed “£500 to buy new instruments”, hey ho there they go again.